Featured Post

Featured Post

Still reeling financially from the coronavirus pandemic, Connecticut’s nursing home industry could face strikes at more than 50 facilities this spring, an industry leader and a key state health official warned Wednesday morning.

And while Gov. Ned Lamont just ordered more emergency aid to cash-strapped facilities, the state’s largest nursing home coalition said the support — while appreciated — falls short of what’s needed.

Meanwhile, the state’s largest health care workers union said Wednesday the pandemic has taken a horrific toll on its members, claiming lives and leaving low-paid and poorly insured workers with nowhere to turn for help.

“I am not forecasting that [a strike] will happen, but I do want to say that is a major concern, a major threat,” Matthew Barrett, president and CEO of the Connecticut Association of Health Care Facilities, told the state’s Nursing Home Financial Advisory Committee.

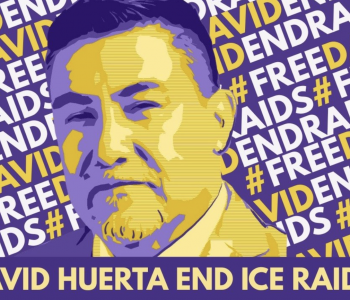

Kara O’Dwyer, center, and other protestors with health care union SEIU 1199, ask police to release detained protestors in Hartford recently. About 100 protestors gathered to ask for better treatment of nursing home, long-term care, home care, group home workers, including health insurance, better wages and proper PPE. – YEHYUN KIM :: CTMIRROR.ORG

Barrett, whose association represents more than 140 facilities, said about 4,500 workers and as many as 30% of all nursing home residents could be affected if a strike happens.

“We would have … a very different type of public health emergency,” he added. “We are urging everyone to stay at the bargaining table.”

Staffing shortages have become common during the pandemic as facilities struggle to entice workers to stay in high-risk, low-paying jobs.

And with family visits greatly limited for much of the past year, Barrett noted, staff have assumed an even larger role in providing emotional support to residents.

SEIU District 1199 New England, which represents about 5,000 nursing home workers in the state, confirmed that members at 51 facilities across Connecticut are working under contracts that expired March 15.

And between now and early 2022, that number could grow to 63 nursing homes, said union spokesman Pedro Zayas.

Kate McEvoy, chairwoman of the advisory committee and director of the Division of Health Services within the Department of Social Services, said the administration has been contacted by some homes worried about their ability to secure contingency staff during the pandemic.

But McEvoy quickly added the state is committed to “dynamic partnership” with the industry to ensure that patient care is maintained in the event of a strike.

“Active planning is happening,” said Barbara Cass, who heads facility licensing and investigations for the state Department of Public Health. She added that the state has escalated its training program to help nursing homes develop strike contingency plans.

Staffing agencies that normally would help nursing homes arrange for strike contingency workers “are very much tapped out because of COVID,” said Nicole Godburn, a manager within the Division of Health Services who also works closely with nursing homes.

An industry in crisis

Nursing homes in Connecticut have lost millions of dollars since the pandemic struck 13 months ago, due not only to increased health, safety and staffing expenses but also because of lost revenue. A significant portion of the industry’s revenue comes from patients temporarily assigned to homes for rehabilitation or recovery after surgery, yet the pandemic led many patients to delay operations and procedures whenever possible.

Lawrence G. Santilli, chairman of the Connecticut Association of Health Care Facilities, warned Lamont in a March 22 letter that the industry has entered an unprecedented time of financial instability.

Nursing home occupancy is down 15% from pre-pandemic levels, and federal and state Medicaid funding has long been inadequate to meet patient care costs.

On average, more than 80% of nursing home revenues involve patients whose care is covered by federal and state Medicaid dollars. Before the pandemic, though, that share was closer to 70%.

“Many nursing homes are forecasting cash shortages on the immediate horizon,” Santilli wrote, adding that some facilities already have taken advantage of state-provided flexibility to defer their health care provider tax payments.

“The financial situation for several of our members is really dire,” Mag Morelli, who heads the state’s other major nursing home coalition, told the CT Mirror after Wednesday’s meeting.

Morelli, who is president of LeadingAge Connecticut, said many homes are losing money monthly and agreed with Barrett that cash flow problems could hinder facilities’ ability to pay bills within a matter of months.

The Lamont administration notified nursing homes Monday of another major round of relief that includes a 5% Medicaid rate increase for the months of April through June, which means an extra $14.1 million for the industry. The state also will delay implementation of a new rate system for nursing homes, which could reduce funding for some facilities, from July 1 to October 1.

It also will continue to cover nursing homes’ testing costs, an expense of about $48 million per year. And facilities that care for COVID-19 patients continue to receive a special daily “hardship” payment of $600 per patient.

CT’s health care workers can’t afford health care

But others say the nursing home industry’s financial woes pale in comparison to the pains Connecticut’s health care workers have faced since COVID-19 battered the state.

Rob Baril, president of SEIU 1199 New England, said 22 union members in long-term health care work were killed by the coronavirus, and others brought the disease home and watched it claim the lives of loved ones.

Many nursing homes and other long-term care workers faced the early stages of the pandemic with “almost complete” lack of access to masks, gowns and other protective gear, Baril said, yet are rewarded by a Connecticut health care system “that traps workers in poverty.”

Many earn less than $30,000 per year and have very poor health insurance that nonetheless costs thousands of dollars per month in premiums, he said.

The union, which began informational picketing Wednesday at nursing homes owned by the Genesis HealthCare chain, held a live-streamed press conference urging state legislators to endorse a health care workers’ Bill of Rights.

This includes a $20-per-hour minimum wage by 2023 and affordable health and child care for all long-term care workers, along with policies to ensure these employees can retire securely.

“What does it say about our health care system when our frontline health care workers cannot afford health care?” said Comptroller Kevin P. Lembo, who joined union members at the press conference.

Lembo, a former state health care advocate, is spearheading a push for legislators to adopt a “public option” health plan. This includes a state-sponsored plan for employees of small businesses and nonprofits, a tax on insurers and additional subsidies for people who buy their insurance on Connecticut’s health exchange, Access Health CT.