Renee Morgan, a housekeeper at a nursing home in St. Louis, caught Covid-19 in late April and considered herself lucky. Her case was mild.

Her quarantine wasn’t. Morgan, 57, was stunned to learn that her employer, Blue Circle Rehab and Nursing, would not give her sick pay while she was out. She’s had to figure out how to cover her bills while waiting for the negative test results she needs to return to work.

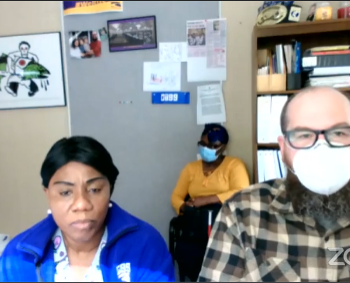

“We’re here caring for somebody’s grandmother. We’re front-line workers, too,” said Morgan, who has worked at the facility for 19 years. She earns a little more than $10 an hour plus one week of paid time off each year – time she’s already burned through. She’s now into her third week without pay. “I hurt so bad because it’s not right.”

“Workers have been feeling the brunt of this,” said U.S. Representative Jan Schakowsky, an Illinois Democrat. She has proposed legislation to protect nursing-home workers, including a requirement for two weeks of paid sick leave. “Their work isn’t valued enough, and these working conditions make it very difficult for them to do their jobs.”

Dangerous Incentive

In the absence of universal testing for Covid-19, federal guidance calls for ill nursing-home workers to stay out of work until they’re symptom free — no fever, no cough — for 72 hours before returning to work. Cutting off their pay gives them a dangerous incentive to return to work early, while they may still be contagious.

Nursing assistants, the most common workers in nursing homes, make a median wage of $13.38 per hour, according to a 2019 study by PHI, a Bronx-based nonprofit that advocates for better caregiver jobs. That’s less than half the average U.S. hourly earnings for workers in all industries, according to federal data. Many nursing assistants don’t have enough savings to forgo weeks of income.

“Many of these workers are well below the poverty level,” said Charlene Harrington, professor emeritus at the University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing. “They have families to support, so they can’t afford to take time off.”

Some operators are backstopping ill workers. The Grand Healthcare System, for instance, estimates it has paid Covid sick leave for 250 employees, about 10% of the workforce at its 16 nursing homes in New York, according to Bruce Gendron, the company’s vice president of labor relations.

Several operators who haven’t provided paid leave, including the owners of Blue Circle Rehab in St. Louis, which employs Renee Morgan, didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment. The handful who did respond say they’ve been devastated by the coronavirus.

“Without the infusion of federal dollars, our business would be insolvent,” said Andrew Weisman, president and chief executive officer of NuVision Management, which runs six nursing homes in Florida and one in New Jersey. NuVision has received $4.8 million in federal health-care assistance, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Increased Costs

Workers from at least one NuVision facility, Tamarac Rehabilitation and Health Center near Miami, have been quarantined without pay after contracting the virus. The center, which normally houses 100 to 110 patients, now has about 60, Weisman said, while other NuVision homes have seen occupancy fall by 25 to 50%. Meanwhile, costs are rising. NuVision spent $250,000 more than usual in the last two months on protective equipment, including masks, he said.

Weisman said the company recently received more government aid — a forgivable loan from the Small Business Administration in an amount that he declined to disclose — that will enable it to compensate staff members who miss work due to Covid-19. “These are employees that we care about,” he said. “We’ve been trying very hard to keep them whole.” However, the company won’t be able to pay workers retroactively for missed time, he said.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which President Donald Trump signed in March, requires employers to provide two weeks of paid leave to workers who are forced to quarantine because of Covid-19. The government covers the cost for companies with fewer than 500 employees through tax credits.

But wary of staff shortages, Congress wrote the law to allow health-care providers to declare themselves exempt from the paid-leave requirement, and the U.S. Department of Labor determined that nursing homes would qualify for the exemption.

Among health workers, those in nursing homes may be the hardest hit by the exclusion.

“These workers tend to have the least amount of power,” said Hina Shah, associate professor of law at Golden Gate University and director of the Women’s Employment Rights Clinic. “They’re low-wage workers, they are often immigrant women.”

In Illinois, where unionized workers threatened to go on strike at 64 locations in May, they received only a relatively modest concession: five days of additional paid sick leave, not enough to cover a typical Covid-19 quarantine.

‘Really Stressful’

Timothy Showman, a 20-year-old housekeeper who earns $8.70 an hour working six days a week at a nursing home in Geneva, Ohio, had to forgo two weeks of pay. In early April, after he was exposed to a resident who tested positive for the virus, a supervisor instructed Showman to stay out of work — without pay — for the next 14 days. The loss of almost $800 was “really stressful,” said Showman, who tested negative for the virus. (Showman provided an email from his employer verifying his account, but asked that his company not be named for fear of retaliation.)

The federal government, meanwhile, has declined to put conditions on the billions of dollars in coronavirus aid it has given to health-care providers. When officials delivered the first funds in April, about $2.6 billion went to nursing homes. “There are no strings attached,” Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, said April 7. “Health-care providers that are receiving these dollars can essentially spend that in any way that they see fit.”

When the Trump Administration delivered $4.9 billion more to the nation’s 15,000 nursing homes on May 22, it required only that recipients agree to use the money “to prevent, prepare for, and respond to coronavirus,” according to terms and conditions posted by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The conditions specifically allowed recipients to offset revenues lost due to the pandemic.

The bailouts have left industry watchdogs uneasy. “This is about preserving the profits of the nursing homes,” said Brian Lee, executive director of Austin-based nonprofit Families for Better Care. “Part of that money should go to ensuring employees on the front lines are safe.”

Palm Garden Healthcare runs 14 nursing homes in Florida with nearly 2,000 beds. The chain’s homes received more than $4 million from the federal government in April, and they’re slated to receive $5.5 million more, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Like many nursing-home chains, Palm Garden offers workers a certain amount of paid time off, or PTO, in addition to their hourly wages. For instance, a worker on the job from one to two years can accrue as much as 6.5 hours of PTO during a two-week pay period, according to union officials. Workers can eventually cash the time in for vacations or use it when they’re sick.

Palm Garden has told workers that the same policies apply during the pandemic: “Team members that are quarantined will be required to adhere to our policy and use PTO when they are out for any reason,” wrote Rita Donovan, Palm Garden’s vice president of human resources, in an April email to union reps. Donovan suggested in that message that Covid-stricken workers who depleted their accumulated time off could use donated time from co-workers, or borrow from PTO that they’d earn in the future.

Workers who’ve already wiped out their PTO accounts question the fairness of that policy. One housekeeper, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution, tested positive in early April after she cleaned the room of an infected resident. To keep her $10-per-hour paycheck coming, she depleted more than 70 hours of PTO, leaving her little flexibility to take any time off this year. “I got the sickness working there, so they should pay me for it,” she said.

Palm Garden’s executives didn’t respond to numerous interview requests.

Advocates say workers shouldn’t have to shoulder the cost of going to work in uniquely risky places during a pandemic. “This isn’t a cold that they picked up in the community,” said Kezia Scales, director of policy research at PHI, the nonprofit that works on behalf of caregivers. “They’re becoming infected as a result of these risks. They should be supported in getting better without taking a large financial hit.”

Written by Ben Elgin